How large an army will be depends largely on the ability of state to support the army – and in premodern times, that was very limited, as agriculture was not efficient enough to support a large non-agricultural population, let alone finance war. Armies are expensive. How large army was exactly depended on nature of the army and its composition. A state where soldiers were given land for their service, such as Byzantine Empire or feudal states, armies could reach around 2,5% of population if they were primarily comprised of infantry, and around 1-1,5% of population if armies were primarily cavalry. A state where army was fully professional usually had even fewer troops: Roman Empire could only maintain around 1,3 – 2% of population in the army despite it being primarily infantry and having to exert crushing taxes (with far more infantry than the Byzantine army used in previous example – some 80 – 85% compared to 50 – 70% for Byzantine period). The highest point was in 395 AD, when population of 16,5 million in the East supported an army of 335 000, for proportion of soldiers of 2,0%. Just before thematic system was introduced, proportion of the soldiers was initially around 1,2% in 641., with 129 000 soldiers supported from a population of 10,5 million. Both of these actually included significant numbers of land-owning limitanei troops, and thus were not truly full professional armies. Arab and Slavic conquests however induced losses, with army being reduced to 80 000 men in 773., defending population of 7 million people – a proportion of 1,14%. This then steadily climbed as financial situation improved and the army shifted from cavalry-centric to an infantry-centric force, allowing an increase to 283 000 men in 1025.. With population of 12 million, this army represented 2,4% of the population of the Empire.

In 15th century, total army of the kingdom will have been around 1% of the population due to predominance of very heavy cavalry. Hungarian kingdom of Jagellonian period could have raised between 70 000 and 100 000 soldiers, from population of 4 to 5 million in total, for a proportion of 1,4 – 2%. At least 30 000 – 45 000 of those were noble levy, which were of limited military utility and likely almost nearly untrained, and in times of need kingdom could raise another 60 000 – 70 000 “troops” in the form of mass levy of peasants. Total number was thus 130 000 – 170 000, or 3 – 4% of populace. Had all these troops been professionals (such as Byzantine tagmata) or semi-professionals (such as Byzantine themata), their numbers will have been lower. As it was, kingdom could only count on 36 000 – 43 000 professional and semi-professional soldiers, counting some 0,9 – 1,1% of the population.

These numbers can be checked by comparing them with available data on military lands:

- German army (15th century)

- hufe: 165 241 m2 (could be as low as 100 000).

- 10 hufen to support a light cavalryman = 1 652 410 m2

- 20 hufen to support a knight = 3 304 820 m2

- Hungarian army (15th century)

- acre: 4047 m2 of land

- Peasant household: 5 people, 30 acres of land = 121 405 m2 (120 000 m2)

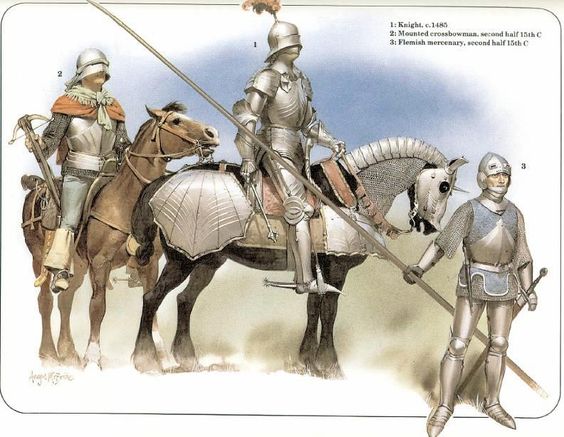

- Mounted crossbowman = 1 per 20 plots; 1 per 10 plots in Transylvania

- Light cavalryman = 1 per 10 plots; 1 per 20 plots in 1524

- Man-at-arms = 1 per 36 plots = 4 370 580 m2

- Light cavalry

- 1 per 12 plots in 1464. = 1 456 860 m2

- 1 per 10 plots in 1524. = 1 214 050 m2

Further assumption will be made that the army is organized into Burgundian lances consisting of a man of arms, a coutillier (light cavalryman), three mounted crossbowmen, as well as two crossbowmen and a pikeman, plus a non-combatant page. Assumption may be made that each infantryman requires two peasant households for support, as a single household could only provide a light infantryman. This means that a lance would require a total of 8 889 450 – 10 656 586 m2 for support (3 304 820 – 4 370 580 m2 for a man-at-arms, 1 214 050 – 1 652 410 m2 for a light cavalryman, 1 214 050 m2 for a mounted crossbowman, and 242 810 – 330 482 m2 for each infantryman). Rural populace in such a feudal society would be between 85% and 95% of total, with higher proportion more likely as increase in size and number of cities weakens feudalism. Taking 90% proportion, it follows that for each 1 000 000 inhabitants there would be 180 000 peasant households with 21 852 900 000 m2. This would allow for support of 2 050 – 2 458 lances for each million inhabitants, for an army of 2 050 – 2 458 heavy lancers (knights / men-at-arms), 2 050 – 2 458 light lancers, 6 150 – 7 374 mounted crossbowmen, 4 100 – 4 916 foot crossbowmen, and 2 050 – 2 458 pikemen. This means that each 1 000 000 inhabitants allows for a force of 18 450 – 19 664 soldiers, of which 10 250 – 12 290 cavalry and 6 150 – 7 374 infantry. In terms of proportion, this force would thus number 1,8 – 2,0% of the total.

This however assumes that all the land is used for supporting the army. This is clearly unrealistic: even a feudal society required significant finances for administrative and other functions. The only difference was that those functions were outsorced to the feudal magnates. Magnates themselves also used land for purposes other than raising troops, and kings in 15th century also started hiring – much more reliable yet also much more expensive – mercenaries. Thus the proportion above can be easily halved in most cases.

Above however concerns only professional soldiers: either full-time or part-time professionals. Militia-based army will be much more numerous, while an army of foreign mercenaries will be much less so. During the Second Punic War, Rome drafted at most 7,5% of population in 215 BC, 9,4% in 214 BC, and 11,9% in 212 BC. In Second Mithridatic War of 83 – 81 BC, mobilization rates were around 8,3%. Greek poleis also had infantry militias which achieved similar mobilization rates. Much later, in 1760. and again in 1813., Prussia mobilized 6 – 7% of total population for service, while Sweden had 7,7% of population under arms in 1709. Confederate states however, which like Rome had access to massive numbers of slaves, managed to mobilize some 11% of the free population between 1861. and 1865. Overall, no preindustrial culture managed to put much more than 7-10% of total population under arms for a campaign season (90 days or so), and only professionals could be kept in the field year-round, numbering not much more than 2% of total population, and usually far fewer.

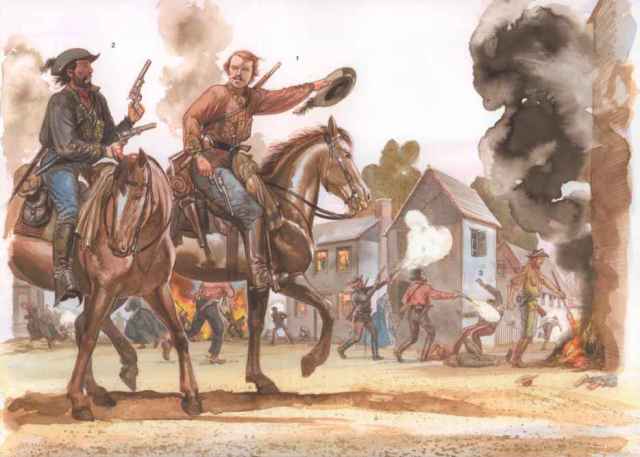

All of the above concerns exclusively military as such: that is, the overall armed forces of the state. But these forces will never (or almost never) be deployed all in one place. First, there are very real logistical constraints on deployments (this will be adressed later). Second, army has to protect rest of the country, as well as keep order. As such, an army will typically deploy no more than half of its total manpower in field armies. Byzantine Empire in 1025. could raise 250 000 soldiers, which translated into deploying two armies of 40 000 men each (or four of 20 000, etc.). Thus an army of 100 000 men will generally be able to deploy 32 000 men in its field armies on a regular basis, though in a “do-or-die” situation force deployed may indeed account for a significant portion (but never the entirety) of the military power of the kingdom. At Battle of Mohacs, Hungarian army numbered some 25 000 soldiers, of which 15 000 cavalry and 10 000 infantry. If total army might have numbered 60 000, then this represents 42% of the total military potential – and it should be kept in mind that significant forces were en route that were not able to join in time. Another important lesson from the Battle of Mohacs relates to the survivability of troops. While cavalry outnumbered infantry 15 000 to 10 000, only 2 000 of the infantry survived – and all of them were captured, making infantry losses to 10 000 out of 10 000. By comparison, only around 4 000 cavalry were lost. This is similar to the outcome of Battle of Kosovo, 78 years earlier, where the entirety of Hungarian infantry was first pushed into wagenburg and then cut down to the last man, while much of cavalry escaped.

Pingback: Building a Fantasy Army Part 6: Numbers | Archer's Aim

Pingback: Building a Fantasy Army – Elves – War Fantasy